A History of Modern Psychology 11th Edition Chapter 12 Quizlet

Summary

The European Recovery Program (ERP), more commonly known as the Marshall Plan (the Plan), was a program of U.S. assistance to Europe during the period 1948-1951. The Marshall Plan—launched in a speech delivered by Secretary of State George Marshall on June 5, 1947—is considered by many to have been the most effective ever of U.S. foreign aid programs. An effort to prevent the economic deterioration of postwar Europe, expansion of communism, and stagnation of world trade, the Plan sought to stimulate European production, promote adoption of policies leading to stable economies, and take measures to increase trade among European countries and between Europe and the rest of the world. Since its conclusion, some Members of Congress and others have periodically recommended establishment of new "Marshall Plans"—for Central America, Eastern Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, and elsewhere.

Design. The Marshall Plan was a joint effort between the United States and Europe and among European nations working together. Prior to formulation of a program of assistance, the United States required that European nations agree on a financial proposal, including a plan of action committing Europe to take steps toward solving its economic problems. The Truman Administration and Congress worked together to formulate the European Recovery Program, which eventually provided roughly $13.3 billion ($143 billion in 2017 dollars) of assistance to 16 countries.

Implementation. Two agencies implemented the program, the U.S.-managed Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA) and the European-run Organization for European Economic Cooperation. The latter helped ensure that participants fulfilled their joint obligations to adopt policies encouraging trade and increased production. The ECA provided dollar assistance to Europe to purchase commodities—food, fuel, and machinery—and leveraged funds for specific projects, especially those to develop and rehabilitate infrastructure. It also provided technical assistance to promote productivity, offered guaranties to encourage U.S. private investment, and approved the use of local currency matching funds.

Accomplishments. While, in some cases, a direct connection can be drawn between American assistance and a positive outcome, for the most part, the Marshall Plan may be viewed best as a stimulus that set off a chain of events leading to a range of accomplishments. At the completion of the Marshall Plan period, European agricultural and industrial production were markedly higher, the balance of trade and related "dollar gap" much improved, and significant steps had been taken toward trade liberalization and economic integration. Historians cite the impact of the Marshall Plan on the political development of some European countries and on U.S.-Europe relations. European Recovery Program assistance is said to have contributed to more positive morale in Europe and to political and economic stability, which helped diminish the strength of domestic communist parties. The U.S. political and economic role in Europe was enhanced and U.S. trade with Europe boosted.

Although the Marshall Plan has its critics and occurred during a unique point in history, many observers believe it offers lessons that may be applicable to contemporary foreign aid programs. This report examines aspects of the Plan's formulation and implementation and discusses its historical significance. The Appendix lists numerous related studies and publications.

The Marshall Plan and the Present1

Between 1948 and 1951, the United States undertook what many consider to be one of its more successful foreign policy initiatives and most effective foreign aid programs. The Marshall Plan (the Plan) and the European Recovery Program (ERP) that it generated involved an ambitious effort to stimulate economic growth in a despondent and nearly bankrupt post-World War II Europe, to prevent the spread of communism beyond the "iron curtain," and to encourage development of a healthy and stable world economy.2 It was designed to accomplish these goals by achieving three objectives:

- the expansion of European agricultural and industrial production;

- the restoration of sound currencies, budgets, and finances in individual European countries; and

- the stimulation of international trade among European countries and between Europe and the rest of the world.

It is a measure of the positive impression enduring from the Economic Recovery Program that, ever since, in response to a critical situation faced by some regions of the world or some problem to be solved, there are periodic calls for a new Marshall Plan. In the 1990s, some Members of Congress recommended "Marshall Plans" for Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union, and the environment. Meanwhile, international statesmen suggested Marshall Plans for the Middle East and South Africa. In the 21st century, there continue to be recommendations for Marshall Plan-like assistance programs—for refugees, urban infrastructure, Iraq, countries affected by the Ebola epidemic, the U.S.-Mexican border, Greece, and so on.3

Generally, these references to the memory of the Marshall Plan are summonses to replicate its success or its scale, rather than every, or any, detail of the original Plan. The replicability of the Marshall Plan in these diverse situations or in the future is subject to question. To understand the potential relevance to the present of an event that took place decades ago, it is necessary to understand what the Plan sought to achieve, how it was implemented, and its resulting success or failure. This report looks at each of these factors.

Formulation of the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was proposed in a speech by Secretary of State George Marshall at Harvard University on June 5, 1947, in response to the critical political, social, and economic conditions in which Europe found itself at that time. Recognizing the necessity of congressional participation in development of a significant assistance package, Marshall's speech did not present a detailed and concrete program. He merely suggested that the United States would be willing to help draft a program and would provide assistance "so far as it may be practical for us to do so."4 In addition, Marshall called for this assistance to be a joint effort, "initiated" and agreed by European nations. The formulation of the Marshall Plan, therefore, was, from the beginning, a work of collaboration between the Truman Administration and Congress, and between the U.S. Government and European governments. The crisis that generated the Plan and the legislative and diplomatic outcome of Marshall's proposal are discussed below.

The Situation in Europe

European conditions in 1947, as described by Secretary of State Marshall and other U.S. officials at the time, were dire. Although industrial production had, in many cases, returned to prewar levels (the exceptions were Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands), the economic situation overall appeared to be deteriorating. The recovery had been financed by drawing down on domestic stocks and foreign assets. Capital was increasingly unavailable for investment. Agricultural supplies remained below 1938 levels, and food imports were consuming a growing share of the limited foreign exchange. European nations were building up a growing dollar deficit. As a result, prospects for any future growth were low. Trade between European nations was stagnant.5

Having already endured years of food shortages, unemployment, and other hardships associated with the war and recovery, the European public was now faced with further suffering. To many observers, the declining economic conditions were generating a pessimism regarding Europe's future that fed class divisions and political instability. Communist parties, already large in major countries such as Italy and France, threatened to come to power.

The potential impact on the United States was severalfold. For one, an end to European growth would block the prospect of any trade with the continent. One of the symptoms of Europe's malaise, in fact, was the massive dollar deficit that signaled its inability to pay for its imports from the United States.6 Perhaps the chief concern of the United States, however, was the growing threat of communism. Although the Cold War was still in its infancy, Soviet entrenchment in Eastern Europe was well under way. Already, early in 1947, the economic strain affecting Britain had driven it to announce its withdrawal of commitments in Greece and Turkey, forcing the United States to assume greater obligations to defend their security. The Truman Doctrine, enunciated in March 1947, stated that it was U.S. policy to provide support to nations threatened by communism. In brief, the specter of an economic collapse of Europe and a communist takeover of its political institutions threatened to uproot everything the United States claimed to strive for since its entry into World War II: a free Europe in an open-world economic system. U.S. leaders felt compelled to respond.

How the Plan Was Formulated

Three main hurdles had to be overcome on the way to developing a useful response to Europe's problems. For one, as Secretary of State Marshall's invitation indicated, European nations, acting jointly, had to come to some agreement on a plan. Second, the Administration and Congress had to reach their own concordance on a legislative program. Finally, the resulting plan had to be one that, in Marshall's words, would "provide a cure rather than a mere palliative."7

The Role of Europe

Most European nations responded favorably to the initial Marshall proposal. Insisting on a role in designing the program, 16 nations attended a conference in Paris (July 12, 1947) at which they established the Committee of European Economic Cooperation (CEEC). The committee was directed to gather information on European requirements and existing resources to meet those needs. Its final report (September 1947) called for a four-year program to encourage production, create internal financial stability, develop economic cooperation among participating countries, and solve the deficit problem then existing with the American dollar zone. Although Europe's net balance of payments deficit with the dollar zone for the 1948-1951 period was originally estimated at roughly $29 billion, the report requested $19 billion in U.S. assistance (an additional $3 billion was expected to come from the World Bank and other sources).8

Cautious not to appear to isolate the Soviet Union at this stage in the still-developing Cold War, Marshall's invitation did not specifically exclude any European nation. Britain and France made sure to include the Soviets in an early three-power discussion of the proposal. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union and, under pressure, its satellites, refused to participate in a common recovery program on the grounds that the necessity to reveal national economic plans would infringe on national sovereignty and that the U.S. interest was only to increase its exports.

CEEC formulation of its proposal was not without U.S. input. Its draft proposal had reflected the wide differences existing between individual nations in their approach to trade liberalization, the role of Germany, and state controls over national economies. As a result of these differences, the United States was afraid that the CEEC proposal would be little more than a shopping list of needs without any coherent program to generate long-term growth. To avoid such a situation, the State Department conditioned its acceptance of the European program on participants' agreement to

- 1. make specific commitments to fulfill production programs,

- 2. take immediate steps to create internal monetary and financial stability,

- 3. express greater determination to reduce trade barriers,

- 4. consider alternative sources of dollar credits, such as the World Bank,

- 5. give formal recognition to their common objectives and assume common responsibility for attaining them, and

- 6. establish an international organization to act as coordinating agency to implement the program.

The final report of the CEEC contained these obligations.

Executive and Congressional Roles

After the European countries had taken the required initiative and presented a formal plan, both the Administration and Congress responded. Formulation of that response had already begun soon after the Marshall speech. As a Democratic President facing a Republican-majority Congress with many Members highly skeptical of the need for further foreign assistance, Truman took a two-pronged approach that greatly facilitated development of a program: he opened his foreign policy initiative to perhaps the most thorough examination prior to launching of any program and, secondly, provided a perhaps equally rare process of close consultation between the executive and Congress.9

From the first, the Truman Administration made Congress a player in the development of the new foreign aid program, consulting with it throughout the process (see text box). A meeting on June 22, 1947, between key congressional leaders and the President led to creation of the Harriman, Krug, and Nourse committees. Secretary of Commerce Averell Harriman's committee, composed of consultants from private industry, labor, economists, etc., looked at Europe's needs. Secretary of Interior Julius A. Krug's committee examined those U.S. physical resources available to support such a program. The group led by Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers Edwin G. Nourse studied the effect an enlarged export burden would have on U.S. domestic production and prices. The House of Representatives itself formed the Select Committee on Foreign Aid, led by Representative Christian A. Herter, to take a broad look at these issues.10

Before the Administration proposal could be submitted for consideration, the situation in some countries deteriorated so seriously that the President called for a special interim aid package to hold them over through the winter with food and fuel, until the more elaborate system anticipated by the Marshall Plan could be authorized. Congress approved interim aid to France, Italy, and Austria amounting to $522 million in an authorization signed by President Truman on December 17, 1947. West Germany, also in need, was still being assisted through the Government and Relief in Occupied Areas (GARIOA) program.

State Department proposals for a European Recovery Program were formally presented by Truman in a message to Congress on December 19, 1947. He called for a 4¼-year program of aid to 16 West European countries in the form of both grants and loans. Although the program anticipated total aid amounting to about $17 billion, the Administration bill, as introduced by Representative Charles Eaton, chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, in early 1948 (H.R. 4840) provided an authorization of $6.8 billion for the first 15 months. The House Foreign Affairs and Senate Foreign Relations Committees amended the bill extensively. As S. 2202, it passed the Senate by a 69-17 vote on March 13, 1948, and the House on March 31, 1948, by a vote of 329 to 74. The bill authorized $5.3 billion over a one-year period. On April 3, 1948, the Economic Cooperation Act (title I of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1948, P.L. 80-472) became law. The Appropriations Committee conference allocated $4 billion to the European Recovery Program in its first year.11

By restricting the authorization to one year, Congress gave itself ample opportunity to oversee European Recovery Program implementation and consider additional funding. Three more times during the life of the Marshall Plan, Congress would be required to authorize and appropriate funds. In each year, Congress held hearings, debated, and further amended the legislation. As part of the first authorization, it created a joint congressional "watchdog" committee to follow program implementation and report to Congress.

Securing the Marshall Plan12

The congressional role in the Marshall Plan is a perhaps useful lesson in achieving passage of a controversial piece of legislation. The Truman Administration's challenge was to obtain support from Congress for a program that would cost taxpayers more than $13 billion.

The Administration and Congress appeared to face a country disinclined to offer such support. World War II had required enormous economic sacrifices from the American people. Between the war's end and mid-1947, the United States had already provided about $11 billion in European relief aid. Isolationist sentiment was strong, and people wanted to be left alone to enjoy that era's peace dividend. Public sentiment strongly favored postwar tax cuts and salary increases.

If the economic environment did not favor a new aid program, the political situation was even more challenging. A Democratic President faced a Republican Congress. Complicating matters, 1948 was a presidential election year in which members of both parties thought the President vulnerable. Reviewing the prospects for the Marshall Plan legislation, Senator Arthur Vandenberg, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, wrote " ... our friend Marshall is certainly going to have a helluva time down here on the Hill when he gets around to his ... plan. It is going to be next to impossible to keep any sort of unpartisan climate in respect to anything. Politics is heavy in the air."13

During the national debate that followed, some Members of Congress considered the Marshall Plan "a socialist blueprint" and "money down a rat hole." Some argued that funds would be better spent on building up defenses or increasing education spending. The Plan, it was said, would accelerate inflation, increase taxation, and cost every man, woman, and child in America $129. Federal workers, the nation's school teachers, children, disabled veterans, and the aged could forget long-sought salary increases or benefits if funds were diverted to pay for the Plan. Moreover, as one Member warned, the Marshall Plan might "wreck the financial solvency of this Government engulfing the nation in poverty and chaos."14

In the face of such criticism, it was incumbent upon U.S. policymakers to assure the American people that the Marshall Plan was workable, that it was well thought out, and that it would ultimately benefit them. The Truman Administration knew it had to win over the American people if it was to have any chance of winning Congress. But the early signs were not encouraging. Public opinion polls in the early autumn of 1947 showed that half of Americans had heard of the Marshall Plan, and, of those who had, many were opposed. Nonetheless, by December, two-thirds had heard of the Plan and only 17% were opposed. What happened in the interim was a huge public education campaign. The Administration sponsored a major public relations effort in support of the Plan. Government officials, including many Cabinet members, crossed the country giving speeches.

One key to success was the organization of a grassroots Citizens' Committee for the Marshall Plan, chaired by former Secretary of War and State Henry Stimson and former Secretary of War Robert Patterson. Its membership of over 300 prominent Americans delivered speeches, wrote newspaper articles, and lobbied Congress. The committee circulated petitions throughout the country and financed women's groups which, in turn, held meetings and sponsored speeches. Eventually, most of the nation's business, farm, religious, and other interest groups came to support the Marshall Plan, including the National Farmers' Union, the Daughters of the American Revolution, League of Women Voters, the American Bar Association, and the National Education Association.

Congress was widely viewed as the real target of all this activity, and the Administration went to great lengths to win its support. The Administration included Congress in development of the European Recovery Program legislation from its earliest stages. Secretary Marshall spent so many hours with Senator Vandenberg that he later said, "We could not have gotten much closer unless I sat in Vandenberg's lap or he sat in mine."15 Historians agree that such cooperation paid off. The highly respected Vandenberg, himself a one-time isolationist, was chiefly responsible for shaping the legislation so that it would move smoothly through the Senate without restricting amendments. As the Washington Post said at the time, "If Marshall was the prophet, Vandenberg has been the engineer..."16

To impress both public and Congress, the Administration set up three high-level committees, each headed by a Cabinet member, which barraged them with detailed reports on the positive impact of the Marshall Plan. The most notable of these was the President's Committee on Foreign Aid, better known as the Harriman Committee, for its chair, the Secretary of Commerce Averell Harriman. Suggested by Vandenberg as a way to soften up Congress, the bipartisan committee was top-heavy with industrialists to ease congressional qualms that the Plan was a "socialist idea." The committee studied the needs of Europe and the shape of the program and ultimately concluded that the Marshall Plan would be good for American business.

All in all, between Administration and outside studies, a Senate Foreign Relations Committee report noted, "it is probable that no legislative proposal coming before the Congress has ever been accompanied by such thoroughly prepared documentary materials."17 Similar observations were repeated frequently throughout the congressional debate to bolster the view that the Administration proposal was sound and should be supported.

Commentators suggest that Congress took its role in the matter quite seriously. The Select Committee on Foreign Aid—freshman Richard Nixon among them—journeyed to Europe to conduct a study. Some of its members went to 22 countries in six weeks. In addition, the State Department sponsored congressional tours, so that by the autumn of 1947, over 214 Members of Congress had visited Europe to examine the situation.

In January 1948, as Congress considered the Marshall Plan legislation, both houses held comprehensive hearings. The Senate held 30 days of them, with nearly 100 governmental witnesses whose testimony fills 1,466 pages. The House heard 85 witnesses in 27 days of testimony filling 2,269 pages.

The Administration, historians note, twisted arms, swapped favors, and offered "pork" to persuade Members to support the Marshall Plan. It also used every argument it could find—the Plan was a way to prevent war and reduce the need for more military spending, it was an act of humanitarian relief, it would encourage a United States of Europe, it would open markets for U.S. goods.18 Finding the communist threat to be the most compelling rationale, the State Department published a file of documents in January 1948 that conclusively confirmed Stalin and Hitler's 1939 plans to divide Europe, further fueling distrust of the Soviet Union.19

In the end, what won the day was the preparation, the bipartisanship, and an obliging Soviet Union, which, shortly before the legislative debate, masterminded a coup in Czechoslovakia and, some suggest, the death of prominent democratic figure Jan Masaryk. Congress passed the Marshall Plan by a wide margin.20

Implementation of the Marshall Plan

Funding and Recipients

In its legislative form as the European Recovery Program (ERP), the Marshall Plan was originally expected to last four and one-quarter years from April 1, 1948, until June 30, 1952. However, the duration of the "official" Marshall Plan, as well as amounts expended under it, are matters of some disagreement. In the view of some, the program ran until its projected end-date of June 30, 1952. Others date the termination of the Plan approximately six months earlier, when its administrative agent, the Economic Cooperation Agency (ECA), was terminated and its recovery programs were meshed with those of the newly established Mutual Security Agency (a process that began during the second half of 1951).

Table 1. Funds Made Available to ECA for European Economic Recovery

(in current $ millions)

| Funds Available | April 3, 1948, to June 30, 1949 | July 1, 1949, to June 30, 1950 | July 1, 1950, to June 30, 1951 | Total |

| Direct Appropriations a | 5,074.0 | 3,628.4 | 2,200.0 | 10,902.4 |

| Borrowing Authority (loans) b | 972.3 | 150.0 | 62.5 | 1,184.8 |

| Borrowing Authority (investment guaranty program) c | 150.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 200.0 |

| Funds Carried Over from Interim Aid | 14.5 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 21.2 |

| Transfers from Other Agencies d | 9.8 | 225.1 | 217.0 | 451.9 |

| TOTAL | 6,220.6 | 4,060.2 | 2,254.1 e | 12,534.9 |

Source: Extracted from William Adams Brown, Jr. , and Redvers Opie, American Foreign Assistance, p. 247. Brown and Redvers compiled this table from figures made available by the budget division of ECA and from figures published in the Thirteenth Report of ECA, p. 39 and 152; and Thirteenth Semiannual Report of the Export-Import Bank for the Period July-December 1951, App. I, p. 65-66.

a. The Foreign Aid Appropriation Act of 1949 appropriated $4 billion for 15 months but authorized expenditure within 12 months. The Foreign Aid Appropriation Act of 1950 contained a supplemental appropriation of $1,074 million for the quarter April 2 to June 30, 1949, and an appropriation of $3,628.4 million for fiscal 1950. The General Appropriation Act of 1951 appropriated $2,250 million for the European Recovery Program for FY1951, but the General Appropriation Act of 1951, Section 1214, reduced the funds appropriated for the ECA by $50 million, making the appropriation for FY1951, $2,200 million.

b. The Economic Cooperation Act of 1948 authorized the ECA to issue notes for purchase by the Secretary of the Treasury not exceeding $1 billion for the purpose of allocating funds to the Export-Import Bank for the extension of loans, but of this amount, $27.7 million was reserved for investment guaranties. The Foreign Aid Appropriation Act of 1950 increased the amount of notes authorized to be issued for this purpose by $150 million. The General Appropriation Act of 1951 authorized the Administrator to issue notes up to $62.5 million for loans to Spain, bringing the authorized borrowing power for loans to $1,184.8 million.

c. The Economic Cooperation Act of 1948 was amended in April 1949 to provide additional borrowing authority of $122.7 million for guaranties. The Economic Cooperation Act of 1950 increased this authority by $50 million, making the total $200 million for investment guaranties.

d. Transfers from other agencies included from Greek-Turkish Aid funds, $9.8 million; from GARIOA funds (Germany), $187.2 million; from MDAP funds, $254.9 million. The Foreign Aid Appropriation Act of 1950 and the General Appropriation Act of 1951 authorized the President to transfer the functions and funds of GARIOA to other agencies and departments. Twelve million dollars was transferred to ECA from GARIOA under Section 5(a) of the Economic Cooperation Act of 1950 and the remainder under the President's authority. The Mutual Defense Assistance Act of 1949 appropriated funds to the President, who was authorized to exercise his powers through any agency or officer of the United States. Transfers to ECA were made by executive order.

e. Total subtracts $225.4 million in transfers to other agencies (July 1950 to June 1951). Transfers to other agencies included $50 million to the Yugoslav relief program, $75.4 million to the Far Eastern program, and $100 million to India. The transfer to Yugoslavia was directed by the Yugoslav Emergency Relief Assistance Act of December 29, 1950. The transfer to the Far Eastern program was made by presidential order (presidential letters of March 23, April 13, May 29, and June 14, 1951). The transfer to India was made by presidential order (presidential letter of June 15, 1951).

Estimates of amounts expended under the Marshall Plan range from $10.3 billion to $13.6 billion.21 Variations can be explained by the different measures of program longevity and the inclusion of funding from related programs which occurred simultaneously with the ERP. Table 1 contains one estimate of funds made available for the ERP (to June 1951 and omitting the interim funding) and lists the sources of those funds in detail.

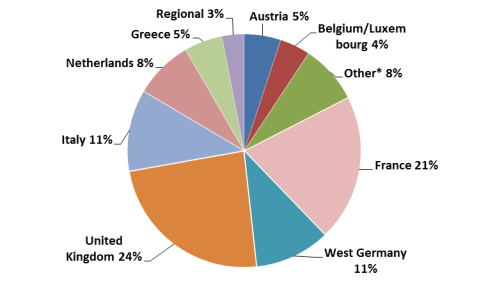

Table 2 lists recipient nations and gives an estimate, based on U.S. Agency for International Development figures, of amounts received at the time. According to this estimate, the top recipients of Marshall Plan aid were the United Kingdom (roughly 25% of individual country totals), France (21%), West Germany (11%), Italy (12%), and the Netherlands (8%) (see Figure 1 ).

| Figure 1. Percentage of Country Allocations |

|

| Source: USAID and CRS calculations. Notes: Other = Denmark, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, and Turkey. |

Table 2. European Recovery Program Recipients: April 3, 1948, to June 30, 1952

(in current $ millions)

| Country | Current Dollars |

| Austria | 677.8 |

| Belgium/Luxembourg | 559.3 |

| Denmark | 273.0 |

| France | 2,713.6 |

| Greece | 706.7 |

| Iceland | 29.3 |

| Ireland | 147.5 |

| Italy | 1,508.8 |

| Netherlands | 1,083.5 |

| Norway | 255.3 |

| Portugal | 51.2 |

| Sweden | 107.3 |

| Turkey | 225.1 |

| United Kingdom | 3,189.8 |

| West Germany | 1,390.6 |

| Regional | 407.0 |

| TOTAL | 13,325.8 |

Source: U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Bureau for Program & Policy Coordination, November 16, 1971.

Administrative Agents

The European Recovery Program assumed the need for two implementing organizations, one American and one European. These were expected to continue the dialogue on European economic problems, coordinate aid allocations, ensure that aid was appropriately directed, and negotiate adoption of effective policy reforms.

Economic Cooperation Administration

Due to the complex nature of the recovery program, the magnitude of the task, and the high degree of administrative flexibility desired with regard to matters concerning procurement and personnel, Congress established a new agency—the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA)—to implement the ERP.22 As a separate agency, it could be exempted from many government regulations that would impede flexibility. Another reason for its separate institutional status was a strong distrust by many members of the Republican-majority Congress of a State Department headed by a Democratic Administration. However, because many in Congress were also concerned that the traditional foreign policy authority of the Secretary of State not be impinged, it required that full consultation and a close working relationship exist between the ECA Administrator and the Secretary of State. Paul G. Hoffman was appointed as Administrator by President Truman. A Republican and a businessman (President of the Studebaker Corporation), both requirements posed by the congressional leadership, Hoffman is considered by historians to have been a particularly talented administrator and promoter of the ERP.

A 600-man regional office located in Paris played a major role in coordinating the programs of individual countries and in obtaining European views on implementation. It was the most immediate liaison with the organization representing the participating countries. Averell Harriman headed the regional office as the U.S. Special Representative Abroad. Missions were also established in each country to keep close contact with local government officials and to observe the flow of funds. Both the regional office and country missions had to judge the effectiveness of the recovery effort without infringing on national sovereignty sensitivities.

As required by the ERP legislation, the United States established bilateral agreements with each country. These were fairly uniform—they required certain commitments to meet objectives of the ERP such as steps to stabilize the currency and increase production, as well as obligations to provide the economic information upon which to evaluate country needs and results of the program.

The Organization for European Economic Cooperation

A European body, the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC), was established by agreement of the participating countries in order to maintain the "joint" nature by which the program was founded and reinforce the sense of mutual responsibility for its success. Earlier, the participating countries had jointly pledged themselves to certain obligations (see above). The OEEC was to be the instrument that would guide members to fulfill their multilateral undertaking.

To advance this purpose, the OEEC developed analyses of economic conditions and needs, and, through formulation of a Plan of Action, influenced the direction of investment projects and encouraged joint adoption of policy reforms such as those leading to elimination of intra-European trade barriers.

At the ECA's request, it also recommended and coordinated the division of aid among the 16 countries. Each year the participating countries would submit a yearly program to the OEEC, which would then make recommendations to the ECA. Determining assistance allocations was not an easy matter, especially since funding declined each year. As a result, there was much bickering among countries, but a formula was eventually reached to divide the aid.

Programs

The framers of the European Recovery Program envisioned a number of tools with which to accomplish its ends (see Table 3 ). These are discussed below.

Dollar Aid: Commodity Assistance and Project Financing

Grants made up more than 90% of the ERP. The ECA provided outright grants that were used to pay the cost and freight of essential commodities and services, mostly from the United States. Conditional grants were also provided requiring the participating country to set aside currency so that other participating countries could buy their export goods. This was done to stimulate intra-European trade.

The ECA also provided loans. ECA loans bore an interest rate of 2.5% starting in 1952, and matured up to 35 years from December 31, 1948, with principal repayments starting no later than 1956. The ECA supervised the use of the dollar credits. European importers made purchases through normal channels and paid American sellers with checks drawn on American credit institutions.

The legislation funding the first year of the ERP provided that $1 billion of the total authorized should be available only in the form of loans or guaranties. In 1949, Congress reduced the amount available only for loans to $150 million. The Administrator had decided that loans in excess of these amounts should not be made because of the inadvisability of participating countries assuming further dollar obligations, which would increase the dollar gap the Plan was attempting to close. As of June 30, 1949, $972.3 million of U.S. aid had been in the form of loans, while $4.948 billion was in the form of grants. Estimates for July 1949 to June 1950 were $150 million in loans and $3.594 billion for grants.23

Table 3. Estimated Expenditures Under the ERP, by Type

(in current $ billions)

| Total Grants: | 11.70 |

| General Procurement (Commodity Assistance) | (11.11) |

| Project Financing | (0.56) |

| Technical Assistance | (0.03) |

| Loans (Commodity Assistance) | 1.14 |

| Guaranties | 0.03 |

| Counterpart Funds (equivalent in U.S. dollars) | 8.60 |

Source: CRS calculations based on Opie and Brown, American Foreign Assistance; Wexler, The Marshall Plan Revisited; State Department and Congressional documents.

The content of the dollar aid purchases changed over time as European needs changed. From a program supplying immediate food-related goods—food, feed, fertilizer, and fuel—it eventually provided mostly raw materials and production equipment. Between early 1948 and 1949, food-related assistance declined from roughly 50% of the total to only 27%. The proportion of raw material and machinery rose from 20% to roughly 50% in this same time period.24

Project financing became important during the later stages of the ERP. ECA dollar assistance was used with local capital in specific projects requiring importation of equipment from abroad. The advantage here was leveraging of local funds. By June 30, 1951, the ECA had approved 139 projects financed by a combination of U.S. and domestic capital. Their aggregate cost was $2.25 billion, of which only $565 million was directly provided by Marshall Plan assistance funds.25 Of these projects, at least 27 were in the area of power production and 32 were for the modernization and expansion of steel and iron production. Many others were devoted to rehabilitation of transport infrastructure.26

Counterpart Funds

Each country was required to match the U.S. grant contribution: a dollar's worth of its own currency for each dollar of grant aid given by the United States. The participating country's currency was placed in a counterpart fund that could be used for infrastructure projects (e.g., roads, power plants, housing projects, airports) of benefit to that country. Each of these counterpart fund projects, however, had to be approved by the ECA Administrator. In the case of Great Britain, counterpart funds were deemed inflationary and simply returned to the national treasury to help balance the budget.

By the end of December 1951, roughly $8.6 billion of counterpart funds had been made available. Of the approximately $7.6 billion approved for use, $2 billion was used for debt reduction as in Great Britain and roughly $4.8 billion was earmarked for investment, of which 39% was in utilities, transportation, and communication facilities (electric power projects, railroads, etc.), 14% in agriculture, 16% in manufacturing, 10% in coal mining and other extractive industries, and 12% in low-cost housing facilities. Three countries accounted for 80% of counterpart funds used for production purposes—France (half), West Germany, and Italy/Trieste.27

Five percent of the counterpart funds could be used to pay the administrative expenses of the ECA in Europe as well as for purchase of scarce raw materials needed by the United States or to develop sources of supply for such materials. Up to August 1951, more than $160 million was committed for these purposes, mostly in the dependent territories of Europe. For example, enterprises were set up for development of nickel in New Caledonia, chromite in Turkey, and bauxite in Jamaica.28

Technical Assistance

Technical assistance was also provided under the ERP. A special fund was created to finance expenses of U.S. experts in Europe and visits by European delegations to the United States. Funds could be used only on projects contributing directly to increased production and stability. The ECA targeted problems of industrial productivity, marketing, agricultural productivity, manpower utilization, public administration, tourism, transportation, and communications. In most cases, countries receiving such aid had to deposit counterpart funds equivalent to the dollar expenses involved in each project. Through 1949, $5 million had been set aside for technical assistance under which 350 experts had been sent from the United States to provide services and 481 persons from Europe had come to the United States for training. By the end of 1951, with more than $30 million expended, over 6,000 Europeans representing management, technicians, and labor had come to the United States for periods of study of U.S. production methods.29

Although it is estimated that less than one-half of 1% of all Marshall Plan aid was spent on technical assistance, the effect of such assistance was significant. Technical assistance was a major component of the "productivity campaign" launched by the ECA. Production was not merely a function of possessing up-to-date machinery, but of management and labor styles of work. As one Senate Appropriations staffer noted, "Productivity in French industry is better than in several other Marshall-plan countries but it still requires four times as many man-hours to produce a Renault automobile as it does for a Chevrolet, and the products themselves are hardly comparable."30 To attempt to bring European production up to par, the ECA funded studies of business styles, conducted management seminars, arranged visits of businessmen and labor representatives to the United States to explain American methods of production, and set up national productivity centers in almost every participating country.31

Investment Guaranties

Guaranties were provided for convertibility into dollars of profits on American private sector investments in Europe. The purpose of the guaranties was to encourage American businessmen to invest in the modernization and development of European industry by ensuring that returns could be obtained in dollars. The original ERP Act covered only the approved amount of dollars invested, but subsequent authorizations broadened the definition of investment and increased the amount of the potential guaranty by adding to actual investment earnings or profits up to 175% of dollar investment. The risk covered was extended as well to include compensation for loss of investment due to expropriation. Although $300 million was authorized by Congress (subsequently amended to $200 million), investment guaranties covering 38 industrial investments amounted to only $31.4 million by June 1952.32

How Programs Contributed to Aims

The individual components of the European Recovery Program contributed directly to the immediate aims of the Marshall Plan. Dollar assistance kept the dollar gap to a minimum. The ECA made sure that both dollar and counterpart assistance were funneled toward activities that would do the most to increase production and lead to general recovery. The emphasis in financial and technical assistance on productivity helped to maximize the efficient use of dollar and counterpart funds to increase production and boost trade. The importance to future European growth of this infusion of directed assistance should not be underestimated. During the recovery period, Europe maintained an investment level of 20% of GNP, one-third higher than the prewar rate.33 Since national savings were practically zero in 1948, the high rate of investment is largely attributable to U.S. assistance.

But the aims of the Marshall Plan were not achieved by financial and technical assistance programs alone. The importance of these American-sponsored programs is that they helped to create the framework in which the overall OEEC European program of action functioned. American aid was leveraged to encourage Europeans to come together and act, individually and collectively, in a purposeful fashion on behalf of the three themes of increased production, expanded trade, and economic stability through policy reform.

The first requirement of the Marshall Plan was that European nations commit themselves to these objectives. On an individual basis, each nation then used its counterpart funds and American dollar assistance to fulfill these objectives. They also, with the analytical assistance of both fellow European nations under the OEEC and the American representatives of the ECA, closely examined their economic systems. Through this process, the ECA and OEEC sought to identify and remove obstacles to growth, to avoid unsound national investment plans, and to promote adoption of appropriate currency levels. Thanks to American assistance, many note, European nations were able to undertake recommended and necessary reforms at lesser political cost in terms of imposing economic hardship on their publics than would have been the case without aid. In this regard, some argue that it was Marshall Plan aid that enabled economist Jean Monnet's plan of modernization and reform of the French economy to succeed.34

However, contending with deeply felt sensitivities regarding European sovereignty, U.S. influence on European economic and social decisionmaking as a direct result of European Recovery Program assistance was restricted. Where it controlled counterpart funds for use in capital projects, American influence was considerable. Where counterpart funds were simply used to retire debt to assist financial stability, there was little such influence. Some analysts suggest the United States had minimal control over European domestic policy since its assistance was small relative to the total resources of European countries. But while it could do little to get Europe to relinquish control over exchange rates, on less sensitive issues the United States, many argue, was able to effect change.35 On a few occasions, the ECA did threaten sanctions if participating countries did not comply with their bilateral agreements. Italy was threatened with loss of aid for not acting to adopt recommended programs and, in April 1950, aid was actually withheld from Greece to force appropriate domestic action.36

As a collective of European nations, the OEEC generated peer pressure that encouraged individual nations to fulfill their Marshall Plan obligations. The OEEC provided a forum for discussion and eventual negotiation of agreements conducive to intra-European trade. For Europeans, its existence made the Plan seem less an American program. In line with the American desire to foster European integration, the OEEC helped to create the "European idea." As West German Vice-Chancellor Blucher noted, "The OEEC had at least one great element. European men came together, knew each other, and were ready for cooperation."37 The ECA provided financial assistance to efforts to encourage European integration (see below), and, more importantly, it provided the OEEC with some financial leverage of its own. By asking the OEEC to take on a share of responsibility for allocating American aid among participating countries, the ECA elevated the organization to a higher status than might have been the case otherwise and thereby facilitated achievement of Marshall Plan aims.

The Sum of Its Parts: Evaluating the Marshall Plan

How the Marshall Plan Was Different

Assistance to Europe was not new with the Marshall Plan. In fact, during the 2½-year period from July 1945 to December 1947, roughly $11 billion had been provided to Europe, compared with the estimated $13 billion in 3½ years of the Marshall Plan. Two factors that distinguish the Marshall Plan from its predecessors are that the Marshall Plan was the result of a thorough planning process and was sharply focused on economic development. Because the earlier, more ad hoc and humanitarian relief-oriented assistance had made little dent on European recovery, a different, coherent approach was put forward. The new approach called for a concerted program with a definite purpose. The purpose was European recovery, defined as increased agricultural and industrial production; restoration of sound currencies, budgets, and finances; and stimulation of international trade among participating countries and between them and the rest of the world. The Marshall Plan, as illustrated in the preceding section, ensured that each technical and financial assistance component contributed as directly as possible to these long-range objectives.

Other aspects of its deliberate character were distinctive. It had definite time and monetary limits. It was made clear at the start that the U.S. contribution would diminish each year. In addition to broad objectives, it also supported, by reference to the CEEC program in the legislation and, more specifically, in congressional report language, the ambitious quantitative targets assumed by the participating countries.38

The Marshall Plan was also a "joint" effort. By bringing in European nations as active participants in the program, the United States ensured that their mutual commitment to alter economic policies, a necessity if growth was to be stimulated, would be translated into action and that the objective of integration would be further encouraged. The Marshall Plan promoted recognition of the economic interdependence of Europe. By making Congress a firm partner in the formulation of the program, the Administration ensured continued congressional support for the commitment of large sums over a period of years.

Further, the Marshall Plan was a first recognition by U.S. leaders of the link between economic growth and political stability. Unlike previous postwar aid, which was two-thirds repayable loans and one-third relief supplies, Marshall Plan aid was almost entirely in the form of grants aimed at productive, developmental purposes. The reason for this large infusion of grants in peacetime was that U.S. national security had been redefined as containment of communism. Governments whose citizens were unemployed and unfed were unstable and open to communist advancement. Only long-term economic growth could provide stability and, as an added benefit, save the United States from having to continue an endless process of stop-gap relief-based assistance.

The unique nature of the Marshall Plan is perhaps best emphasized by what replaced it. The Cold War, reinforced by the Korean War, signaled the end of the Marshall Plan by altering the priority of U.S. aid from that of economic stability to military security. In September 1950, the ECA informed the European participants that henceforth a growing proportion of aid would be allocated for European rearmament purposes. Although originally scheduled to end on June 30, 1952, the Plan began to wind down in December 1950 when aid to Britain was suspended. In the following months, Ireland, Sweden, and Portugal graduated from the program. The use of counterpart funds for production purposes was phased out. To attack inflation, which resulted from the shortage of materials due to the Korean War, the ECA had begun to release counterpart funds. In the fourth quarter of 1950, $1.3 billion was released, two-thirds of which were used in retiring public debt.

Under the Mutual Security Act of 1951 and subsequent legislation, although in lesser quantities and in increasing proportions devoted to defense, aid continued to be provided to many European countries. In the 1952-1953 appropriations, for example, France received $525 million in grants, half of which was for defense support and the other as budget support. The joint nature of the Marshall Plan disappeared as national sovereignty came to the fore again. France insisted on using post-Marshall Plan counterpart funds as it wished, commingling them with other funds and only later attributing appropriate amounts to certain projects to satisfy American concerns.

Accomplishments of the Marshall Plan

To many analysts and policymakers, the effect of the Marshall Plan policies and programs on the economic and political situation in Europe appeared broad and pervasive. While, in some cases, a direct connection can be drawn between American assistance and a positive outcome, for the most part, the Marshall Plan may be viewed best as a stimulus which set off a chain of events leading to the accomplishments noted below.

Did It Meet Its Objectives?

The Marshall Plan agencies, the ECA and OEEC, established a number of quantitative standards as their objectives, reflecting some of the broader purposes noted earlier.

Production

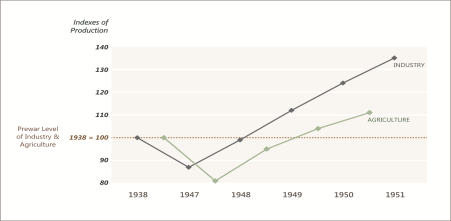

The overall production objective of the European Recovery Program was an increase in aggregate production above prewar (1938) levels of 30% in industry and 15% in agriculture. By the end of 1951, industrial production for all countries was 35% above the 1938 level, exceeding the goal of the program. However, aggregate agriculture production for human consumption was only 11% above prewar levels and, given a 25 million rise in population during these years, Europe was not able to feed itself by 1951.39

Viewed in terms of the increase from 1947, the achievement is more impressive. Industrial production by the end of 1951 was 55% higher than only four years earlier. Participating countries increased aggregate agricultural production by nearly 37% in the three crop-years after 1947-1948. Total average GNP rose by roughly 33% during the four years of the Marshall Plan.40

| Figure 2. Growth in European Production: 1938-1951 |

|

| Source: Brown and Opie, American Foreign Assistance, p. 249 and 253. |

The 1948 Senate report on the ERP authorization had noted a set of production goals that the Europeans had set for themselves, goals that they noted "seem optimistic to many American experts."41 The participating countries, for example, had wanted to increase steel production to 55 million tons yearly, 20% above prewar production. By 1951, they had achieved 60 million. It was proposed that oil refining capacity be increased by 2½ times that in 1938. In the end, they managed a four-fold increase. The goal for coal production was 584 million tons, an increase of 30 million over prewar production. By 1951, production was still slightly below that of 1938, but 27% higher than in 1947.42

Balance of Trade and the Dollar Gap

In 1948, participating countries could pay for only half of their imports by exporting. An objective of the ERP was to get European countries to the point where they could pay for 83% of their imports in this manner. Although they paid for 70% by exporting in 1938, the larger ratio was sought under ERP because earnings from overseas investment had declined.43

Even though trade rose substantially, especially among participants, the volume of imports from the rest of the world rose substantially as well, and prices for these imports rose faster than did prices of exports. As a result, Europe continued to be strained. One obstacle to expansion of exports was breaking into the U.S. and South American markets, where U.S. producers were entrenched. OEEC exports to North America rose from 14% of imports in 1947 to nearly 50% in 1952.44

Related to the overall balance of trade was the deficit vi s- a - vis the dollar area, especially the United States. In 1947, the total gold and dollar deficit was over $8 billion. By 1949, it had dropped to $4.5 billion, by 1952 to half that figure, and by the first half of 1953 had reached an approximate current balance with the dollar area.45

Trade Liberalization

In 1949, the OEEC Council asked members to take steps to eliminate quantitative import restrictions. By the end of 1949, and by February 1951, 50% and 75% of quota restrictions on imports were eliminated, respectively. By 1955, 90% of restrictions were gone. In 1951, the OEEC set up rules of conduct in trade under the Code of Liberalization of Trade and Invisible Transactions. At the end of 1951, trade volume within Europe was almost double that of 1947.46

Other Benefits

Some benefits of the Marshall Plan are not easily quantifiable, and some were not direct aims of the program.

Psychological Boost

Many believe that the role of the Marshall Plan in raising morale in Europe was as great a contribution to the prevention of communism and stimulation of growth as any financial assistance. As the then-Director of Policy Planning at the State Department George Kennan noted, "The psychological success at the outset was so amazing that we felt that the psychological effect was four-fifths accomplished before the first supplies arrived."47

Economic Integration48

The United States had a view of itself as a model for the development of Europe, with individual countries equated with American states. As such, U.S. leaders saw a healthy Europe as one in which trade restraints and other barriers to interaction, such as the inconvertibility of currencies, would be eliminated. The European Recovery Program required coordinated planning for recovery and the establishment of the OEEC for this purpose. In 1949, the ERP Authorization Act was amended to make it the explicit policy of the United States to encourage the unification of Europe.49 Efforts in support of European integration, integral to the original Marshall Plan, were strengthened at this time.

To encourage intra-European trade, the ECA in its first year went so far as to provide dollars to participating countries to finance their purchase of vitally needed goods available in other participating countries (even if these were available in the United States). In a step toward encouraging European independence from the dollar standard, it also established an intra-European payments plan whereby dollar grants were made to countries that exported more to Europe as a group than they imported, on condition that these creditor countries finance their export balance in their own currencies.

The European Payments Union (EPU), an outgrowth of the payments plan, was established in 1950 by member countries to act as a central clearance and credit system for settlement of all payments transactions among members and associated monetary areas (such as the sterling area). At ECA request, the 1951 congressional authorization withheld funds specifically to encourage the pursuit of this program since successful conclusion of the EPU depended on an American financial contribution. In the end, the United States provided $350 million to help set up the EPU and another $100 million to assist it through initial difficulties. Many believe that these and other steps initiated under the ERP led to the launching of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1952 and eventually to the European Union of today.

Stability and Containment of Communism

Perhaps the greatest inducement to the United States in setting up the Marshall Plan had been the belief that economic hardship in Europe would lead to political instability and inevitably to communist governments throughout the continent. In essence, the ERP allowed economic growth and prosperity to occur in Europe with fewer political and social costs. Plan assistance allowed recipients to carry a larger import surplus with less strain on the financial system than would be the case otherwise. It made possible larger investments without corresponding reductions in living standards and could be anti-inflationary by mopping up purchasing power through the sale of imported assistance goods without increasing the supply of money. The production aspects of the Plan also helped relieve hunger among the general population. Human food consumption per capita reached the prewar level by 1951. In West Germany, economically devastated and besieged by millions of refugees from the East, one house of every five built since 1948 had received Marshall Plan aid.50

Perhaps as a result of these benefits, communism in Europe was prevented from coming to power via the ballot box. It is estimated that communist strength in Western Europe declined by almost one-third between 1946 and 1951. In the 1951 elections, the combined pro-Western vote was 84% of the electorate.51

U.S. Domestic Procurement

Champions of the Marshall Plan hold that its authorizing legislation was free of most of the potential restrictions sought by private interests of the sort to later appear in foreign aid programs. Nevertheless, restrictions were enacted that did benefit the United States and U.S. business in particular.

Procurement of surplus goods was encouraged under the Economic Recovery Program legislation, while procurement of goods in short supply in the United States was discouraged. It was required that surplus agriculture commodities be supplied by the United States; procurement of these was to be encouraged by the ECA Administrator. The ERP required that 25% of total wheat had to be in the form of flour, and half of all goods had to be carried on American ships.52

In the end, an estimated 70% of European purchases using ECA dollars were spent in the United States.53 Types of commodities purchased from the United States included foodstuffs (grain, dairy products), cotton, fuel, industrial and raw materials (iron and steel, aluminum, copper, lumber), and industrial and agricultural machinery. Sugar and nonferrous metals made up the bulk of purchases from outside the United States.

Enhanced Role in Europe for the United States

U.S. prestige and power in Europe were already strong following World War II. In several respects, however, the U.S. role in Europe was greatly enhanced by virtue of the Marshall Plan program. U.S. private sector economic relations grew substantially during this period as a consequence of the program's encouragement of increased exports from Europe and ERP grants and loans for the purchase of U.S. goods. The book value of U.S. investment in Europe also rose significantly. Furthermore, while the Marshall Plan grew out of a recognition of the economic interdependence of the two continents, its implementation greatly increased awareness of that fact. The OEEC, which, in 1961, became the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) with the United States as a full member, endured and provided a forum for discussion of economic problems of mutual concern. Finally, the act of U.S. support for Europe and the creation of a diplomatic relationship which centered on economic issues in the OEEC facilitated the evolution of a relationship centered on military and security issues. In the view of ECA Administrator Hoffman, the Marshall Plan made the Atlantic Alliance (NATO) possible.54

Proving Ground for U.S. Development Programs

Many of the operational methods and programs devised and tested under the Marshall Plan became regular practices of later development efforts. For example, the ECA was established as an independent agency with a mission in each participating country to ensure close interaction with governments and the private sector, a model later adopted by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Unlike previous aid efforts, the Plan promoted policy reform and used commodity import programs and counterpart funds to ease adoption of those reforms and undertake development programs, a practice of USAID programs in later decades. The Marshall Plan also launched the first participant training programs bringing Europeans to the United States for training and leveraged private sector investment in recipient countries through the use of U.S. government guaranties. Hundreds of American economists and other specialists who implemented the Marshall Plan gained invaluable experience that many later applied to their work in developing countries for the ECA's successor foreign aid agencies.

Critiques of the Marshall Plan

Not everyone agrees that the Marshall Plan was a success. One such appraisal was that Marshall Plan assistance was unnecessary. It is, for example, difficult to demonstrate that ERP aid was directly responsible for the increase in production and other quantitative achievements noted above. Critics have argued that assistance was never more than 5% of the GNP of recipient nations and therefore could have little effect. European economies, in this view, were already on the way to recovery before the Marshall Plan was implemented.55 Some analysts, pointing out the experimental nature of the Plan, agree that the method of aid allocation and the program of economic reforms promoted under it were not derived with scientific precision. Some claim that the dollar gap was not a problem and that lack of economic growth was the result of bad economic policy, resolved when economic controls established during the Nazi era were eventually lifted.56

Even at the time of the Marshall Plan, there were those who found the program lacking. If Marshall Plan aid was going to combat communism, they felt, it would have to provide benefits to the working class in Europe. Many believed that the increased production sought by the Plan would have little effect on those most inclined to support communism. In congressional hearings, some Members repeatedly sought assurances that the aid was benefiting the working class. Would loans to French factory owners, they asked, lead to higher salaries for employees?57 Journalist Theodore H. White was another who questioned this "trickle" (now called the "trickle down") approach to recovery. "The trickle theory had, thus far," White wrote in 1953, "resulted in a brilliant recovery of European production. But it had yielded no love for America and little diminution of Communist loyalty where it was entrenched in the misery of the continental workers."58

In addition, many did not want the United States to appear to be assisting colonial rule. Considerable concern was expressed that the aid provided to Europe would allow these countries to maintain their colonies in Africa and Asia. The switch in emphasis from economic development to military development that began in the third year of the Plan was also the subject of criticism, especially in view of the limited time frame originally allowed for the aid program. A staff member of the Senate Appropriations Committee's Special Subcommittee on Foreign Economic Cooperation believed that the original intent of the Marshall Plan could not be accomplished under these conditions.59

The tactics employed to achieve Marshall Plan objectives were often questioned as well. "Much of our effort in France has been contradictory," reported the committee staffer. "On the one hand we have been working toward the abolition of trade barriers between European countries and on the other we have been fostering, or rebuilding, uneconomic industries which cannot survive unhampered international competition."60 Another concern was the proportion of funding that went to the public rather than private sector. One contemporary writer noted that public investments from the Italian counterpart fund obtained twice the amount of assistance as did the private sector in that country. Another analyst has argued that the ECA promoted government intervention in the economy.61 In the 1950 authorization hearings, U.S. businessmen urged that assistance be provided directly to foreign business rather than through European governments. Only in this way, they said, could free enterprise be promoted in Europe.62

From its inception, some Members of Congress voiced fears that the ERP would have a negative effect on U.S. business. Some noted that the effort to close the trade gap by encouraging Europeans to export and limit their imports would diminish U.S. exports to the region. Amendments, most defeated, were offered to ERP legislation to ensure that certain segments of the private sector would benefit from Marshall Plan aid. That strengthening Europe economically meant increased competition for U.S. business also was not lost on legislators. The ECA, for example, helped Europeans rebuild their merchant marine fleets and, by the end of 1949, had authorized over $167 million in European steel mill projects, most using the more advanced continuous rolling mill process that had previously been little used in Europe. As the congressional "watchdog" committee staff noted, "The ECA program involves economic sacrifice either in direct expenditure of Federal funds or in readjustments of agriculture and industry to allow for foreign competition."63 In the end, the United States seemed to be willing to make both sacrifices.

Lessons of the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was viewed by Congress, as well as others, as a "new and far-reaching experiment in foreign relations."64 Although in many ways unique to the requirements of its time, analysts have attempted over the years to draw from it various lessons that might possibly be applied to present or future foreign aid initiatives. These lessons represent what observers believe were some of the primary strengths of the Plan:65

- Strong leadership and well-developed argument overc a me opposition. Despite growing national isolationism, polls showing little support for the Marshall Plan, a Congress dominated by budget cutters, and an election looming whose outlook was unfavorable to the President, the Administration decided it was the right thing to do and led a campaign—with national commissions set up and Cabinet members travelling the country—to sell the Plan to the American people.

- Congress was included at the beginning to formulate the program. Because he faced a Congress controlled by the opposition party, Truman made the European Recovery Program a cooperative bipartisan creation, which helped garner support and prevented it from becoming bogged down with private-interest earmarks. Congress maintained its active role by conducting detailed hearings and studies on ERP implementation.

- Country ownership ma de reforms sustainable. The beneficiaries were required to put together the proposal. Because the Plan targeted changes in the nature of the European economic system, the United States was sensitive to European national sovereignty. European cooperation was critical to establishing an active commitment from participants on a wide range of delicate issues.

- The collective approach facilitated success. Recovery efforts were framed as a joint endeavor, with the Europeans joining together in the CEEC to propose the program and the OEEC to implement key features, including collaborating to make grant allocation decisions and cooperating to lower trade barriers.

- The Marshall Plan had specific goals. Resources were dedicated to meeting the goals of increased production, trade, and stability.

- The Marshall Plan fit the objective. In the main, the Plan was not a short-term humanitarian relief program. It was a multiyear plan designed specifically to bring about the economic recovery of Europe and avoid the repeated need for relief programs that had characterized U.S. assistance to Europe since the War.

- The countries to be assisted, for the most part, had the capacity to recover . They, in fact, were recovering, not developing from scratch. The human and natural resources necessary for economic growth were largely available; the chief thing missing was capital.

- Trade supplemented aid. Aid alone was insufficient to assist Europe economically. A report in October 1949 by the ECA and Department of Commerce found that the United States should purchase as much as $2 billion annually in additional goods if Europe was to balance its trade by the close of the recovery program. Efforts to increase intra-European trade, such as funding the European Payments Union, were meant to bolster bilateral efforts.

- Parochial congressional tendencies to put restrictions on the program on behalf of U.S. business were kept under control for the good of the program. American businessmen, for example, were not happy that the ECA insisted Europeans purchase what was available first in Europe using soft currency before turning to the United States.

- Technical assistance, including exchanges, while inexpensive relative to capital block grants, may have a significant impact on economic growth. Under the Marshall Plan, technical assistance helped draw attention to the management and labor factors hindering productivity. It demonstrated American know-how and helped develop in Europe a positive feeling regarding America.

- The long-term foreign policy value of foreign assistance cannot be adequately measured in terms of short-term consequences. The Marshall Plan continues to have an impact: in NATO, the OECD, the European Community, the German Marshall Fund, in European bilateral aid donor programs, and in the stability and prosperity of modern Europe.66

The Marshall Plan as Precedent

Although many disparate elements of Marshall Plan assistance speak to the present, the circumstances faced now by most other parts of the world are so different and more complex than those encountered by Western Europe in the period 1948-1952 that the solution posed for one is not entirely applicable to the other. As noted earlier, calls for new Marshall Plans have continued ever since the first, but the first was unique, and today's proposals share little detail with their predecessor apart from the suggestion that a problem should be solved with the same concentrated energies, if not funds, applied decades ago.

Even if there exist countries whose needs are similar in nature to what the Marshall Plan provided, the position of the United States has changed since the late 1940s as well. The roughly $13.3 billion provided by the United States to 16 nations over a period of less than four years equals an estimated $143 billion in 2017 currency. That sum surpasses the amount of development and humanitarian assistance the United States provided from all sources to 212 countries and numerous international development organizations and banks in the four-year period 2013-2016 ($138 billion in 2017 dollars).67 In 1948, when the United States appropriated $4 billion for the first year of the Marshall Plan, outlays for the entire federal budget equaled slightly less than $30 billion.68 For the United States to be willing to expend 13% of its budget on any one program (versus 0.8% in FY2016 for foreign assistance), Congress and the President would have to agree that the activity was a major national priority.

Nevertheless, in pondering the difficulties of new Marshall Plans, it is perhaps worth considering the views of the ECA Administrator, Paul Hoffman, who noted 20 years after Secretary Marshall's historic speech that even though the Plan was "one of the most truly generous impulses that has ever motivated any nation anywhere at any time," the United States "derived enormous benefits from the bread it figuratively cast upon the international waters." In Hoffman's view:

Today, the United States, its former partners in the Marshall Plan and—in fact—all other advanced industrialized countries ... are being offered an even bigger bargain: the chance to form an effective partnership for world-wide economic and social progress with the earth's hundred and more low-income nations. The potential profits in terms of expanded prosperity and a more secure peace could dwarf those won through the European Recovery Program. Yet the danger that this bargain will be rejected out of apathy, indifference, and discouragement over the relatively slow progress toward self-sufficiency made by the developing countries thus far is perhaps even greater than was the case with the Marshall Plan. For the whole broadscale effort of development assistance to the world's poorer nations—an effort that is generally, but I think quite misleadingly, called "foreign aid"—has never received the full support it merits and is now showing signs of further slippage in both popular and governmental backing. Under these circumstances, the study of the Marshall Plan's brief but brilliantly successful history is much more than an academic exercise.69

Appendix. References

Arkes, Hadley. Bureaucracy, the Marshall Plan, and the N ational I nterest. Princeton University Press, 1972. 395 p.

Behrman, Greg. The Most Noble Adventure: the Marshall Plan and How America Helped Rebuild Europe, New York, Simon and Shuster, 2007, 448 p.

Brookings Institution. Current I ssues in F oreign E conomic A ssistance. Washington, Brookings, 1951. 103 p.

Brown, William Adams, Jr. and Redvers Opie. American F oreign A ssistance. Washington, The Brookings Institution, 1953. 615 p.

Congressional Digest, The Controversy in Congress Over Marshall Plan Proposals: Pro and Con, March 1948.

Cowen, Tyler. "The Marshall Plan: Myths and Realities," in Doug Bandow, ed. U.S. Aid to the Developing World. Washington, Heritage Foundation, 1985. p. 61-74.

Economic Cooperation Administration. The Marshall Plan: a H andbook of the Economic Cooperation Administration. Washington, ECA, 1950. 18 p.

Economic Cooperation Administration. The Marshall Plan: a P rogram of I nternational C ooperation. Washington, ECA, 1950. 63 p.

Foreign Affairs, Commemorative Section, The Marshall Plan and Its Legacy, May/June 1997, Vol 76, Number 3.

Geiger, Theodore. "The Lessons of the Marshall Plan for Development Today," Looking Ahead, National Planning Association, v. 15, May 1967: 1-4.

German Information Center, The Marshall Plan and the F uture of U.S.-European R elations. New York, 1973. 54 p.

Gimbel, John. The O rigins of the Marshall Plan. Stanford University Press, 1976. 344 p.

Gordon, Lincoln. "Recollections of a Marshall Planner." Journal of International Affairs, v. 41, Summer 1988: 233-245.

Hartmann, Susan. The Marshall Plan. Columbus, Merrill Publishing Co., 1968. 70 p.

Hitchens, Harold L. "Influences on the Congressional Decision to Pass the Marshall Plan," The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 1, March, 1968, p. 51-68.

Hoffmann, Stanley and Charles Maier, eds. The Marshall Plan: a R etrospective. Boulder, Westview Press, 1984. 139 p.

Hogan, Michael J. The Marshall Plan: America, Britain, and the R econstruction of Western Europe, 1947-1952. Cambridge University Press, 1987. 482 p.

Hogan, Michael J. "American Marshall Planners and the Search for a European Neocapitalism." American Historical Review, v. 90, Feb. 1985: 44-72.

Isaacson, Walter and Evan Thomas, The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made, New York, Simon&Schuster, 1986.

Jones, Joseph M. The F ifteen W eeks (February 21-June 5, 1947). New York, Viking Press, 1955. 296 p.

Kostrzewa, Wojciech and Peter Nunnenkamp and Holger Schmieding. A Marshall Plan for Middle and Eastern Europe? Kiel Institute of World Economics Working Paper No. 403, Dec. 1989.

Machado, Barry. In Search of a Usable Past: The Marshall Plan and Post-War Reconstruction Today, George C. Marshall Foundation, Lexington, Virginia, 2007.

Mee, Charles L., Jr. The Marshall Plan: The L aunching of the P ax A mericana. New York, Simon & Schuster, 1984. 301 p.

Milward, Alan S. The R econstruction of Western Europe, 1945-51. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1984. 527 p.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. From Marshall Plan to G lobal I nterdependence. Paris, OECD, 1978. 246 p.

OECD Observer. Special Issue: Marshall Plan 20 th A nniversary. June 1967.

Pfaff, William. "Perils of Policy." Harper's Magazine, v. 274, May 1987: 70-72.

Price, Harry Bayard. The Marshall Plan and its M eaning. Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1955. 424 p.

Quade, Quentin L. "The Truman Administration and the Separation of Powers: the Case of the Marshall Plan. " Review of Politics, v. 27, Jan. 1965: 58-77.